Choreodrome Rehearsals Week 2 – The Casement Project

We’ve already shown movement sketches to the participants in our Micro-rainbow workshops, to a variety of old friends who dropped in to the studio, to the Artist Development team at the Place, and to a paying public in the Touchwood series of scratch performances. Each of these encounters with others have taught me different things: it is one thing to share work with people with whom you have already established a relationship and with whom you’ve begun to build some kind of community. It is another to do that with people who are meeting the work for the first time. How do I ensure that their first encounter is one that draws them closer to the work and that invites them to get to know more about it?

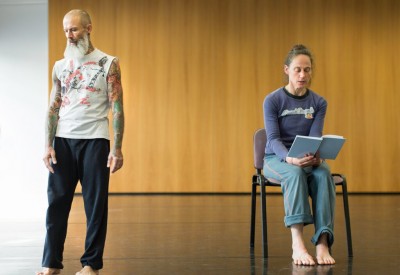

One thing I do know after these openings of the early raw material is that I am fortunate to have such a compelling group of performers, whose individual distinctiveness is matched by a sensitivity to the others (performers and audience) with whom they are sharing the performance. Life experience made legible in their bodies and generously revealed is part of what makes them so special. While I know I have a job of crafting to do to shape with them the environment that an audience will encounter in the work, I am proud that already the heart of the work exists with them.

One of the things I was concerned to test in this Choreodrome research was how the allusive, shifting, dynamic world I wanted to create in the movement, a world in which Casement’s life, afterlife and legacy might be set in motion rather than represented, could work with the radio play that I propose to use as the basis for the sound score. I am using the original BBC production of David Rudkin‘s play, Cries from Casement as His Bones are Brought to Dublin. The play was broadcast in 1973, having been delayed according to Rudkin because of sensitives in Anglo-Irish relations at the time. Its point of departure is the ‘repatriation’ in 1965 to Dublin of Casement’s bones, from the prison yard in Pentonville prison in London. It had been Casement’s wish to be buried in Antrim but such a re-burial wouldn’t have counted as a generous gesture that the British government wanted to make to the Irish Republic in advance of the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Rising. The play is fragmentary and multi vocal, with characters ranging from Dr Crippen to Joan Bakewell. Rudkin read much of Casement’s archive, including his diaries, and noticing the different handwriting styles he found there, imagines a complex, fragmenting, shifting Casement. I’m using the play, because there is much in Rudkin’s approach that is sympathetic to my concern to put the body and its knowledge at the heart of the national narrative. Also the fact that it is a radio play, beautifully designed by the Radiophonic workshop, makes it suitable as a score, something to be listened to, rather than seen. And, with its period BBC and occasionally duff Irish accents, the excellent production nonetheless conveys something of a civilising colonial perspective, an authoritative voice whose authority I wish to complicate by bringing it alongside the dancing. There is perhaps homage and guile in the strategy, a strategy not unfamiliar in the history of Irish literature in English. It is the strategy of the colonised.

Finally, using Rudkin’s play reminds me that no matter how much original archival research that I do, our access to Casement is always mediated, and we construct our version of him in relation to a history of mediation as well as to our own context.